President Harry S. Truman at his desk in the Oval Office signing H.R. 5632, the National Security Act Amendments of 1949, August 10, 1949. No photo is available of the signing of the original 1947 Act because Truman signed it while aboard the presidential aircraft. (Truman Library, Accession Number 73-3205).

Landmark statute established the CIA, the NSC, and the foundations of the Department of Defense – the Underpinnings of the Modern National Security State

Wide-ranging law contributed to a “complete overhaul” of the Executive Branch, transformed U.S. foreign policy making, and empowered America’s global engagement through the Cold War and beyond

Published: Jul 26, 2022 Briefing Book #Compiled and edited by visiting Scoville Fellow Rachel Santarsiero

For more information, contact:

202-994-7000 or nsarchiv@gwu.edu

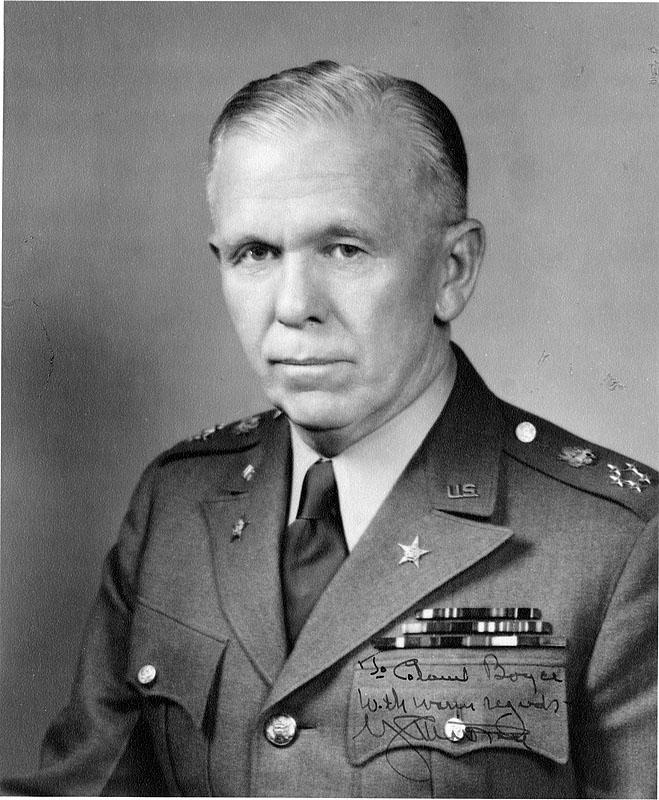

General George C. Marshall in 1945 as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army. In 1947, Marshall became the 50th U.S. Secretary of State. (Truman Library, Accession Number 2014-3569).

Secretary of Navy James Forrestal on February 20, 1946. (Truman Library, Accession Number 99-409).

Truman’s presidential airplane Sacred Cow. The aircraft was often called the “flying Oval Office,” and this is where Truman signs the National Security Act into law on July 26, 1947. (National Archives).

James Forrestal is sworn in as Secretary of Defense by Chief Justice Fred Vinson on September 17, 1947, after the National Security Act goes into effect. Left to right are General Dwight D. Eisenhower, John L. Sullivan, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Senator Stuart Symington, Major General Alfred M. Gruenther, and Thomas J. Hargrave. (Truman Library, Accession Number 97-1766).

President Harry S. Truman with members of his National Security Council on August 19, 1948. (Truman Library, Accession Number 73-2703).

Hide/Unhide SectionWashington, D.C., July 26, 2022 – 75 years ago, President Harry S. Truman signed the National Security Act into law, marking a major restructuring of the U.S. government’s military and intelligence apparatus in the years following World War II. U.S. strategists saw the act as essential for enabling America’s future global mission of protecting and advancing Western interests. The law’s architects could not have foreseen how this fundamental restructuring would revolutionize U.S. policy making in later years, especially after earth-shaking events like 9/11.

But despite its great significance, even at the time the National Security Act was overshadowed by other pronouncements such as the Marshall Plan and the Truman doctrine.

Today, on the law’s 75 th anniversary, the National Security Archive publishes a compilation of key declassified U.S. documents that show the run-up to its enactment, the debates surrounding the unification of the military departments, and the establishment of three major national security organizations: the National Security Council (NSC) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the office of a civilian Secretary of Defense. This publication also sheds light on how the law, originally crafted with the intent of military and intelligence reorganization, evolved into something that would overhaul the Executive branch and establish the essential framework for foreign policy making during and after the Cold War.

Rachel Santarsiero is a Herbert Scoville Jr. Peace Fellow at the National Security Archive.

Following the rise of Nazism, the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the turmoil of World War II, the U.S. emerged as the world’s sole superpower, full of potential, but determined not to allow a perceived global threat—Soviet-led Communism—to dominate the scene. The war had already introduced some valuable organizational experiments—the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, the intelligence and covert actions agency used during the war), and the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee (SWNCC). But with its determination that the U.S. resist a return to isolationism and instead play a leading role in world affairs, the Truman Administration sought to strengthen the nation’s postwar security apparatus with a new set of government structures to better coordinate diplomacy, military operations, and intelligence gathering.[1]

The leadup to the signing of the National Security Act was filled with conflict, controversy, and compromise. Despite shared sentiments for postwar security organizational reform amongst Truman and his officials, the military departments in particular were at odds over what exactly reform should look like, especially regarding a unified armed forces department.

Inspired in part by the level of coordination achieved by the British Committee of Imperial Defense during World War II, many U.S. officials had the topic of military unification on their minds.[2] In April 1945, the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee report “Reorganization of National Defense” recommended a single department of the Armed Forces with a civilian head above a military commander of the armed forces [Document 1]. The army had submitted a similar plan that advocated for centralization, with Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson making the case that a single military department would be more supportive of army programs.[3]

The Navy, seeking to preserve its autonomy, was starkly opposed to unification. Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal feared that a military department funded by a single defense appropriations bill might draw funds away from the Navy. In May 1945, Forrestal tapped Ferdinand Eberstadt, Vice Chairman of the War Production Board, to assess the question of unification. In what was dubbed The Eberstadt Report, the 250-page proposal stressed the need for civil-military coordination but opposed the establishment of a single military department. Eberstadt argued that military unification “looks good on paper,” but in reality, it would not survive “the acid test of modern war.”[4] Both he and Forrestal were also skeptical that a single civilian could run such a large, consolidated department, and Forrestal in particular objected to a plan that would “deprive the navy secretary of a seat in the Cabinet, hence direct access to the president.”[5] As a substitute for consolidation, the report recommended a national security council, making the argument that a council could act as a “policy-forming and advisory, not an executive, body.”[6] Eberstadt’s report was submitted to Congress in October 1945 and was viewed as an alternative to the Army plan [Document 2].

For much of 1945 and the start of 1946, the Army-Navy unification discrepancy dominated the scene. Truman, drawing on his Senate experiences serving on the Military Affairs Committee, was largely pro-unification, and ultimately pressed Patterson and Forrestal to come to an agreement.

Meanwhile, the Air Force, which had long been a part of the Army, was determined to exercise its own independence and even aspired to become a dominant department. In a memorandum that captures these postwar ambitions, Commodore Arleigh A. Burke, then with the Atlantic Command (and a future Chief of Naval Operations), felt compelled to write to the commander-in-chief of the Atlantic Command, Vice Admiral William H.P. Blandy, about a fervent speech given by Army Air Force Brigadier General Frank A. Armstrong in which Armstrong (who “had been drinking but . was by no means under the influence of intoxicating liquor”) bluntly declared that the Air Force would be a “predominant force during the peace … we do not care whether you like it or not, … the Army Air Forces are going to run the show.” [Document 3].

Beyond the matter of armed forces reorganization was the question of what role the intelligence apparatus would play in the foreign affairs and defense establishments. Having endured a war against several dictatorial powers, the American public understandably was wary of the growth of government intrusion in their daily lives. Truman, sharing the public’s sentiments, was adamant about not creating an intelligence bureaucracy that could develop into an American “Gestapo.” However, he and top officials such as Forrestal and Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall understood that a peacetime foreign policy in the postwar landscape had to include institutional reorganization not just for military purposes but also for intelligence reasons.[7] A major impetus for the latter was the experience of Pearl Harbor and the determination not to be caught so dangerously unaware again.

In 1945, the Joint Chiefs of Staff had submitted its own proposal to the president on the formulation of an independent agency, but recommended it be established through presidential directive [Document 4]. To prevent an intelligence apparatus that would “trample on the rights of the American people,” Truman attempted to integrate the OSS into the State Department, effectively designating State as the lead agency in coordinating intelligence.[8] However, State rejected this, and the president instead signed a presidential directive establishing the Central Intelligence Group (CIG) as the overarching intelligence body, replacing the defunct OSS.

The creation of the CIG also ensured that Truman could rely on an intelligence agency responsible to the president rather than the military services. To that end, among other developments, U.S. intelligence began preparing a “daily summary” for the president's eyes only, even before the CIA was officially established."[9] This, however, was a temporary solution and it would take more time for even a preliminary consensus to develop on what the structure and role of the Central Intelligence Agency would be (see below).

After months of army-navy clashes, the two military secretaries ultimately settled on armed forces unification in January 1947. Their proposal gave general authority to a Secretary of National Defense with the caveat that individual secretaries would administer the three departments as separate units. Their plan also outlined agreements on a National Security Council, a Central Intelligence Agency, and a JCS without a single chief or chairperson. A series of Forrestal’s diary entries from February to July 1947 illuminate the Navy’s continued skepticism on the unification bill as it moved through Congress, even after the Patterson-Forrestal agreement [Documents 5-7].

Meanwhile, State remained wary of an independent intelligence agency and a powerful security council. In a memorandum to the president sent in early 1947, now Secretary of State George Marshall cautioned Truman on the ramifications of the latter [Document 8]. Marshall was worried that a council with statutory power and responsibilities would introduce “fundamental changes in the entire question of foreign relations.” Ultimately, the ambiguous language defining the council would later allow each president to use the NSC as he or she saw fit.

Following months of a congressional tug-of-war over the bill, President Truman signed the National Security Act into law on July 26, 1947, codifying the establishment of the National Security Council (NSC), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the merging of the War and Navy Departments as well as the establishment of an independent Department of the Air Force under a new entity called the National Military Establishment. The law also institutionalized the wartime Joint Chiefs of Staff as well as established the National Security Resources Board [Document 9].

Despite the enormous expenditure of time and energy that went into the legislation, in the immediate period following its passage it was clear the National Security Act had serious shortcomings. For example, as one scholar later put it, the section that established the CIA “fulfilled Napoleon’s standards for a good constitution: ‘short and vague’.”[10] On April 30, 1948, a paper written by the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff to the NSC indicated the uncertainty felt by the State Department officials as they tried to figure out how to use the CIA and other governmental organizations, political operations, and “political warfare.” [Document 10]. This document was later followed by NSC 10/2 in June of 1948, which became the official Truman edict on using the CIA and the Office of Policy Coordination to carry out covert operations.[11] Perhaps more fundamentally, the military branches, while housed under the freshly-created National Military Establishment, were hardly unified; the civilian-led Secretary of Defense operated at the mercy of the other military secretaries, possessing much less authority than the Secretary of State wielded; the duties of the CIA were poorly defined (partially contributing to State’s continued authority over matters of intelligence); and the president barely confided in his newly established NSC.

Amidst this confusion, tensions flared among practitioners in the new security landscape outlined by the law. Forrestal, recently appointed the first Secretary of Defense, was particularly discontented. In a moment of grim humor, he predicted, “this office will probably be the greatest cemetery for dead cats in history.”[12] Unable to “overcome the institutional weakness inherent” to his position[13], Forrestal concluded that he “would continue to fail unless his position was strengthened by new legislation.”[14]

Partially as a response to the act’s ambiguities, two independent task forces were created to evaluate the recent reorganization. These recommendations would inspire President Truman to sign the National Security Act Amendments of 1949, establishing the Department of Defense as an Executive Department (replacing the National Military Establishment), that now included the Department of the Army, the Department of the Navy (including the U.S. Marine Corps), and the Department of the Air Force [Document 11]. By strengthening the role of the secretary of defense and centralizing authority within the new Department of Defense, these modifications “completely changed the character of the defense department” and would help revolutionize foreign policy making.[15]

That same year, Truman also signed the Central Intelligence Agency Act of 1949, a piece of legislation that allowed the CIA to secretly fund intelligence operations and develop personnel procedures outside standard U.S. government practices [Document 12]. Along with documents like NSC 10/2, the CIA Act was influenced by the results of other internal discussions, notably the Dulles-Jackson-Correa report of January 1, 1949 [Document 13]. The intelligence act also exempted the CIA from having to disclose its “organization, function, names, officials, titles, salaries, or numbers of personnel employed.” As Clark Clifford, Truman’s administrative assistant, put it later, the CIA became “a government within a government, which could evade oversight of its activities by drawing the cloak of secrecy about itself.”[16] But it was always ultimately responsible to the president, as Clifford himself sought.

The NSC, CIA, and Department of Defense that would emerge and grow in the years following the 1949 amendments would in some respects be almost unrecognizable from the bodies envisioned in 1947. It wasn’t until the war in Korea that the NSC became an integral part of the Executive Office of the President, and each president would use it in slightly different ways. But each well understood its value for centering decision making authority more firmly in the White House and bypassing many of the inevitable political and bureaucratic obstacles to the policy process. As a result, NSC influence would continue to swell in size with each subsequent administration. This trend became evident under Truman’s immediate successor, President Dwight D. Eisenhower. [Document 14] By the time the Cold War ended, the NSC staff and the newly created national security adviser to the president would create an “unassailable position of preeminence” within the national security bureaucracy.[17]

As for the military, by converting the Department of Defense to a cabinet level department, the 1949 amendments ensured that the secretary of defense now held authority over the other military secretaries. Later, provisions like the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act would further enhance the authority of that office, “particularly in the areas of budgets and strategy.”[18] These developments helped pave the way for the increasingly dominant role the defense secretary would come to play in foreign policy matters after the Cold War – most visibly in the years after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Lastly, the power of the CIA in covert operations overseas, specifically after the issuing of NSC 10/2 and the 1949 Central Intelligence Agency Act, continued to grow during the first three decades of the Cold War, not just providing intelligence gathering and analytical functions but carrying out many dozens of covert operations, from influencing elections to helping to overthrow governments and even attempting to assassinate foreign leaders. More recently, a key element of the 1947 National Security Act would be overhauled in 2004 when Congress created the Office of Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), replacing the CIA as the overarching intelligence body.

The National Security Act of 1947 was passed against the backdrop of a changing security landscape fueled by the aftermath of a world war, the rising threat of international communism, and the emergence of phenomena like new technologies. At the time, the authors of the Act were almost certainly unaware of the wide-ranging and long-lasting implications the law would have during the Cold War and beyond.

At present, despite intervening events like 9/11, and the subsequent creation of the Department of Homeland Security and the ODNI, several factors that led to the formulation of the 1947 National Security Act continue to exist—albeit in slightly different forms. Instead of a world war against Nazism, Russia and China represent the largest global threats. Instead of combatting communist ideology, the world has been confronting a tide of international terrorism in the form of extremist groups like al-Qaeda, ISIS, and al-Shabaab. Instead of technologies like radar and overhead reconnaissance, we’re now dealing with the ramifications of cyber technology. These factors have already been inspiring calls for fundamental reorganization today, as they did in 1947.